I found this book at a record shop a long time ago.

It has some good interviews w/ 17 musicians from different styles.

At first I just scanned the Alice Cooper photos then tried

out a free software called PDF OCR X Community Edition

that made me scan the pages & convert to text. Of course it has

a hard time reading punctuations so I had to go through & correct

so if you come across any typos you'll know why.

Rock "N" Roll Asylum by Headley Gritter

Cover - paperback

Back Cover

Pg 5, Contents

this has an interesting group of artists

It's still available on Amazon

Pg 6

page before Introduction

same image as cover only b&w

Pg 8

Alice Cooper section is from

pg 8 to pg 25

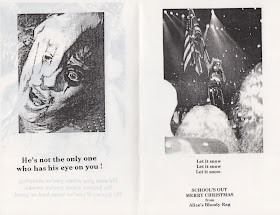

Pg 19

From the moment he began his musical crusade, Alice

Cooper has been the master of the unexpected and

he outrageous. During his humble beginnings around

the sleazy bar circuit of the late Sixties, Alice managed to

disgust more patrons than he would endear. Billed as “The

Worst Band in L.A.,” their potential for provoking response

was spotted by manager extraordinaire Shep Gordon, and

lint other expert on the extreme, Frank Zappa. Zappa

signed them to his newborn “Straight” label, and together

hey released Pretties For You and Easy Actlon. Neither

produced the fame and fortune that had been anticipated,

so Alice and his band headed for their native Detroit,

heavily in debt from their first vinyl experience.

The turning point came in 1970 when Bob Ezrin pro-

duced Love It To Death, which contained the classic‚

“I’m Eighteen”‚ a song described as America’s answer to the

Who’s “My Generation.” Greater success followed with

Killer and School’s Out, and with it came the bizarre stage

machinations which brought Alice infamy. His commercial

peak came in 1973 with Billion Dollar Babies; the tour that

hlowed is still one of the highest grossing in U.S. concert

history - in more ways than one.

But then Alice began a downward slide, both musi-

cally and personally. His shows became more grotesque,

8 he seemed more intent upon out-sickening his past

performances. And perhaps, in an attempt to rid himself of

he stage persona he had created, he sought refuge in the

bottle.

When I spoke with him, he was beginning a new

phase of his career. He had just released “Flush the

Fashion” thereby embracing the New Wave phenomenon.

Accordingly, his live performances shifted from lavish

“DeMillie-ian” exercises in the ludicrous to sparser, more

psyche-oriented presentations.

Alice felt rejuvenated, and liberated from the shack-

hs of alcohol as well. He spoke freely and honestly, con-

fessing all. He also didn’t concern himself with false

modesty-although all praises bestowed on Alice were in

its third person. It is, perhaps, this ability to separate the

private person from the character he created that led to his

physical and emotional rehabilitation. The strain of the

years was evident, however, and Alice appeared much in

need of sun and vitamins.

“Be different”- has this always been your credo?

Number one is the fact that I’ve always looked for a place

that needed to be filled. There’s always been a need for

Alice Cooper. I think there’s always been a need for my

sense of humor and sense of the way I handle the stage.

Now that I have got that, I’ve never heard anybody compare

me to anybody. They compare people to me. I don’t think

they’ve ever compared Alice to somebody else. And that

to me is important right there. Now the thing is to have fun

with it. I took it seriously for a long time, almost had a ner-

vous breakdown, almost drank myself to death. And now

I’m having so much more fun. I’m a Detroit-based rock and

roller, and I’ll always be, and I'm just doing what comes

naturally.

When did you realize you were taking it too seriously?

When I was in the hospital throwing up blood might have

been when I realized I was taking it too seriously. When

rock n’ roll becomes a drudge . . . I went out there to have

fun. I didn’t want to work in my life.

Is that why you got into show business?

Oh yeah. I never had a job in my life. I’ve always been able

to talk my way out of any work. But what I do on stage now

is harder than what anybody else does on stage. The last

show we did was an hour and a half, and I was only off for

three minutes the whole time. So what was non-work

before, is now three times the work, five times the work, but

I love it. I’ve always said that I just refuse to go through this

lifetime without being noticed.

How did your childhood affect your career?

I had the most normal childhood, the best parents, every-

thing like that. The funny thing is, I think that Alice, the

character, had lots of problems. Whoever that character is,

the other side of me, must have had a lot of other crazy

problems, ‘cause he’s the one who’s up on stage. He’s the

one who’s going through all these insanities.

So Alice Cooper was originally a release for the insanity that

you had to control?

Sure. I don’t know where he came from, but there must

have been a lot pent up. I was like Walter Mitty. I still am, a

little bit. But I think I’m tending more towards Alice now. I’m

feeling a lot more comfortable being like Alice.

Did you have any early desire for fame?

I was always famous. When I was in elementary school I

was the most popular kid in the school, because I couldn’t

fight, I was too little, a little teeny guy, but I could talk my

way out of any fight. I always made sure I made friends with

the biggest guy. “Listen, you don’t want to hit me.” Growing

up in Detroit, you had to learn how to take care of yourself.

And I was known as the great diplomat.

Who did you want to emulate on stage when you had those

conceptions of fame?

When I was a kid? I wanted to be Eliot Ness, Zorro, Bela

Lugosi, and Basil Rathbone. And as it turns out, that’s what

Alice turned out to be. A combination of all the great

villains. Alice has very little hero quality in him. You want to

see him tying the girl to the railroad track, you don’t want to

see him rescuing her.

Was there any musician you wanted to emulate?

Oh, yeah. Anybody my parents hated, I loved. The first time

they saw the Rolling Stones, they had this look of true an-

guish and horror, and immediately they were my favorite

group. They had just got used to the Beatles with the suits

on. After that I realized that the Yardbirds and those kinds

of groups were what I really liked. I liked anything that

sounded out of control. The Kinks. Any feedback was

great. Still, any feedback is great.

When did your fascination with the bizarre begin?

When I was born.

But you said you had a normal childhood.

I had a normal childhood to everybody else. But to myself,

there was no doubt in my mind that I was going to be in

show business of some sort. There was no other desire. I

didn’t know what I was going to do. I might have been a

game show host or a cowboy, but I knew it was bent to-

wards show biz. Then when rock n’ roll came along I

said, “whoa, there it is” and I grabbed it.

How did you come up with the name Alice Cooper?

I have no idea. I really don’t. It was one day, just (snaps

fingers) boom. We needed a new name and I said “Why

don’t we call ourselves” . . . and I could have said Mary

Smith, but I said Alice Cooper. And that was the name.

What drug induced “Alice Cooper?”

I don’t know. It was probably just Phoenix air, you know,

Phoenix smog. But think about it-Alice Cooper has the

same kind of ring as Lizzie Borden and Baby Jane. “Alice

Cooper.” It’s sort of like a little girl with an ax. I kept pictur-

ing something in pink and black lace and blood. Mean-

while, people expected a blonde folk singer.

Why a female name?

Well. I don’t know. It was just the kind of thing where, you

know, maybe it’s a possession of some sort.

On one of your early albums, on the back cover, you’re

dressed in drag.

In which one?

Pretties for You.

No, that’s a cheerleader outfit. I used to wear a slip on top,

tucked into Levis jeans. But I think that was more parody.

None of the guys were ever in drag. We got a reputation for

being like that, but we never were. in fact, we had a reputa-

tlon for doing a lot of things that I wish we would have done.

Well. that goes on to the next question, I’m sure the . . .

Chickens.

Not chickens. This is in the general area of. . .

Not the nun question, please . . .

I’m going to have to write that down so I don’t forget. . . the

nun and the chicken, right. I was going to say that you must

have attracted some bizarre types.

Our audiences are like mental cases. They’re great.

You must have attracted some pretty strange groupies as well.

We went through all of 'em. We went through the best ones.

and the most ridiculous ones. This was back when the

groupies were Groupies. There was a top ten groupie

chart. And they were the best. When you got into town, the

band that was there before you would say, “listen, check

her off because you don’t want to be dripping for the next

three weeks. This one here’s fine, she’ll be okay, but, you

know, a little moody.” And that’s not an antifeminist thing, it

was an essential part of rock n’ roll. I respected the ladies

for one reason - they didn’t bullshit around about the whole

thing. They were there for one reason, and they were . . .

They were getting what they wanted

Lots of them were.

What kind of things would they do to attract your attention?

You knew who they were when you walked in. First of all,

they were backstage. How do you get backstage, unless

you’re a pro? The roadies get there first, and they look

around and they immediately say, oh, no. And of course.

the groupies were like celebrities. Certain ones were truly

celebrities, so they were immediately allowed backstage.

The amateurs had to work their way backstage, that’s all.

Just like anything else.

Every rock band has its groupies, but I’m sure the Alice

Cooper groupies would be at the more extreme end of the

spectrum. Would they come in costume?

Oh yeah, always, then and now. And sometimes real

straight, executive looking, you know. Which are the crazi-

est ones? They’re the ones you say to yourself, oh-oh, there

are razor blades in her hair. And each one of them has got

a different sort of . . .

Specialty?

Yeah. And you never can tell. Its very crazy.

What was that about the nun and the chicken?

Oh, nothing, it’s nothing. Something that happened years

ago, really nothing.

All right, I’ll try again later.

Your first gigs were in some pretty sleazy establishments,

weren’t they?

We played every bar there was. and lived in every Holiday

Inn in the country. I started in 1964. when I was sixteen. l

was a sophomore in high school, touring on weekends,

going off to New Mexico or Phoenix, everywhere. There’s a

certain mentality about touring. I look forward to the rotten

hotels now, you know. It’s fun.

What effect did that have on your character? Are you a

stronger person now?

Oh, ask anybody that’s been on the road. You have to deal

with cockroaches as big as your road manager. I woke up

one morning and there was a rat and a cockroach dragging

my guitar into the bathroom.

You didn’t sign them for the next tour?

No, but theyd be good bodyguards. “You guys want to be

in the show?”

When did you meet Frank Zappa? Was he me one that dis-

covered you?

He saw us at this one place where we drove at least six

thousand people out. Back in 1968 or 1969. People were

still into peace and love, and we were never into that, ever.

That picture from “Pretties for You” was normal dress

for us during the day. And that was just to outrage people.

Behind it was all this hard rock that wasn’t in the least bit

pretty. It was very rough, because we believed totally in

hard rock. So the music, combined with our look, was dan-

gerous. I think it was so dangerous that even rock audien-

ces were afraid of it. And most rock bands were also. They

saw that, futuristically, they were going to have to compete

with us, ‘cause first of all it was show biz. And it was getting

a lot of attention.

So how did Zappa find you?

Zappa saw us playing, and he saw all the people leave, and ...

It turned him on . . .

Sure. And Shep, my manager was there, and I think we

cleaned out the place of about six thousand people in the

space of about four songs. And there were maybe ten

people left - Zappa, my manager, and the GTO’s, and they

loved it. You take the negative energy and turn it around,

and you realize how powerful that is.

How would you feel, emotionally, with six thousand people

walking out on you?

We’ve done our job. (Laughter) I didn’t want to play for a

bunch of hippies, you know. Well, we in the group looked at

each other and said, “Boy, we must really be doing some-

thing right here.”

They either love you or they hate you.

You’re in the middle, you might as well not be there. If

you’re going to be gray, forget it. We realized that power,

just that power alone. was going to be important, because

we had something that if the audience would just hold on to

it for a second, they were gonna have to like it. We were

rebelling against everything that everybody believed in. We

held nothing sacred.

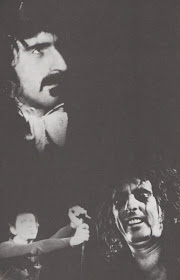

Have you been influenced by Zappa at all?

When I was a kid in Phoenix, Zappa was like a hero. In fact,

I had a little mustache and beard. We were almost identical.

We’ve toured with them sometimes, but I haven’t seen

Frank for a long time. And I like him. I think Frank’s one of

the best guitarists, and he’s got one of the funniest senses

of humor. And we stay away from each other because we’re

almost too close. Maybe he doesn’t want me saying this . . .

“I mean, he’s a rotten guy. And whatever you think about

him is right.”

You were rumored to have had a gross out competition on stage.

That never happened. That’s one of those legends.

What was the actual situation that prompted that exaggeration?

I don’t even know. We used to tour together, which I guess

was enough of a gross out. It was Zappa, Alice Cooper, and

Wild Man Fischer and the GTO’s.l can’t think of anything

more insane than that. But the rumors that come out of

those tours . . . Frank called me one morning and says

“What is this I hear about tearing a chicken’s head off and

drinking all of his blood?” I said “What?!” But I didn’t deny

it, and he says, “It’s all over the papers, you’re getting

banned everywhere.” And I said “Really?” He said, “Keep

up the good work.” Frank’s great . . . he’s one of the best.

Your stage show, as we said earlier, was probably before its time.

Other bands were just going up there and playing guitar and suddenly

you came along with all these accoutrements, giant whiskey bottles and guillotines.

I think Groucho Marx described you as “the last remaining hope for vaudeville.”

Yeah, that was nice of him. The old guys really had a sense

of show business. I met all those guys - Fred Astaire, Jack

Benny and the rest - and the funny thing was that they all

liked the Alice Cooper show. You’d think that they wouldn’t

like the loud music, but they loved it. Because they saw

something that was fresh. When they were doing their own

shtick, they were considered outrageous. And you have to

remember that those guys, or anybody that’s ever been a

superstar, has been a rebel. In their craft. Probably they’ve

been hated first and then liked.

Who thought up the idea of the stage show with the bizarre

underworld overtones?

It was like an extension of my personality, really. And it had

the Alice touch all the way because, if I looked at the stage

and there was something that wasn’t the way that Alice

would do it, I would say “That doesn’t belong.”

Was it like some childhood fantasy you were able to fulfill?

It was a certain period of Saturday morning monster

movies that I never grew out of. I could tell you right now, if

somebody were to show me a stage and say this is the new

Alice Cooper stage, I’d look at it and I’d say, “oh, this goes

here, that goes there,” and it would be arranged the way

that Alice would want it.

Was success sudden when it happened?

Yeah, because first of all, people wanted to like us. It’s fun-

ny - they needed a reason. They wanted to like us, but they

sat there and said, “There’s got to be some reason to like

Alice.” They needed a handle so that they could say safely

to their friends, “Oh, yeah, I like Alice Cooper.” lt’s still like

that. People are afraid to say that theyre Alice Cooper fans.

That’s what the “hit single” is all about, isn’t it?

I don’t think we ever expected to have a hit single. And

we’ve had fifteen of ‘em. So that means that the country

wanted an impish kind of character, a villain that they could

depend on. And I think Alice will always be that. I’ll never be

a hero. But if they want a quote in Newsweek or Time,

they’ll always come to me for that. Alice is, you know, all

American. He speaks for a certain part of everybodys black

humor.

So its basically a desire to shock?

But not only shock. I hate it when people are so set and

they say that this is the only way things can be done. I

absolutely will not go with it. I don’t care what it is. If some-

body tells me it can’t be done any other way, I will go out of

my way to say that you’re crazy. That’s a defiant thing. I just

hate set ways. I’m really not big on tradition at all.

So when was the point at which you felt, “wow, we’ve made it”?

There was a time when I was getting an allowance of twen-

ty dollars a week. And I could actually save money out of

that - because we were all starving, twenty bucks a week

got to be a lot of money for us. This is reality, the fact that

we were starving that much. And it got to the point that

when we first got our “big” checks it didn’t mean anything,

because it was so big that we didn’t understand how much

it was.

Do you enjoy me fame and the recognition now?

Oh yeah, I love it.

Do you like the open doors?

Anybody’d be crazy not to enjoy fame. You do lose a lot of

your privacy. l have to lock myself up in my sanctuary up in

the hills if I want to get any privacy. And still, the tour bus

goes by saying, “On the left we have the snake-riddled

Alice Cooper mansion.” That’s what I wake up to in the

morning. I have lightning machines so it always looks like

it’s raining around my house.

Is the decor “early Addams Family”?

Yeah. And I’ve got a moat around the house.

How did your problems with booze start?

Oh, that took a long time. Drinking started out being just

one of the guys. drinking, drinking, drinking. I didn’t realize,

underneath, that what had happened was that the fun part

of it had suddenly beoorne the gasoline to make it work.

You know what I mean? It was always fun. It you can drink

and have fun, then you’re not going to be an alcoholic. But

if you have to have it to have fun, or to work, then you’ve

lost it, it’s taken you. I would never touch a drink now,

because, like any alcoholic that’s been cured. it’s poison. I

might start drinking all over again. And you know, three

months in the hospital is really a bitch.

Was the album “From The Inside” part of that exorcism?

Oh yeah, I wrote some of that in the hospital. But again,

that was something unusual; I didn’t expect that to be part

of the show - Alice confesses everything, goes up on stage

and says, “Okay, I’m an alcoholic, just like Betty Ford.”

The song “I’m Eighteen” has been described as the “My

Generation” of America. I’ve heard that was written while

you were drunk.

“Eighteen” started out as a jam - we used to play in this

little club and just play those chords over and over, and it

was nothing more than a three chord jarn, until we said,

listen, let’s take the basics of that and make it into a song.

The lyrics weren’t written until we were in the studio. The

lyrics to “Schools Out” weren’t written until we were in the

studio. I very rarely write anything until the last minute be-

cause I like the spontaneity of it. I hate to labor over lyrics.

How do you write?

I just write, with irony in mind. I like to set up a situation and

twist it.

Do you think, “well, a set of lyrics is due, I better sit down

and write them” or do you wait until the moment is right?

I’ll be sitting there, and if a catch line hits me, say, if I’m

watching television and somebody will say “Oh, that guy is

a real model citizen” I’ll go and write “model citizen” down.

“Model citizen.” What a great thing. Alice is a model citizen.

And immediately my mind’s going “Argh,” what an

irony - “A|ice is a model citizen. “People hate Alice Cooper

but they win cars on quiz shows by knowing who he is.

They don’t let their kids go to the concerts but they watch

him on “Hollywood Squares.” What a weird thing. And I

write all this irony down. And then when you read it, it’s

reality, and you go, well, that really is an oddity of life.

Did the song “Only Women Bleed” cause a bit of an uproar

when it came out?

Yeah. And then it became a standard. it’s funny, because at

first, people thought,ol course, that it was about menstrua-

tion. It’s kind of a sympathetic song. And it was a Tennessee

Williams kind of way of saying it, you know. I thought

“Only Women Bleed” would havevbeen something that

Tennessee Williams would have said. And I like to honor

certain writers, dedicating certain things to them. So I wrote

that whole song with a Tennessee Williams thing in mind.

There seem to be two facets of your writing, but the ballad

side seems totally unrelated to the rock side.

Yeah. Well, how do you relate “I’m Down” by the Beatles to

“Yesterday”? There’s no comparison at all.

Do you have to be in the right frame of mind to write a ballad?

It’s much easier to write a ballad than it is to write a rock

‘n’ roll song. A good original rock and roll song is really

hard to write. Think of all the albums that have been out.

Think of all the writing that’s been done. I can’t think of any-

thing original. It depends on your technique, and how you

do it.

How did your association with Elton John’s Iyricist, Bernie

Taupin come about?

Oh, we’ve been friends for ten years. And nobody would

expect Bernie and I, two lyricists especially, to get together.

And Elton and I, I mean, he’s my next door neighbor. So l

go over every once in a while and borrow a cup of diamonds.

Why didn’t you write with him?

Well, because, in the Seventies if you think about it, the four

or five names that stand out in the Seventies were the more

flamboyant characters. And there was a certain competi-

tiveness that was always there between Elton, myself,

Bowie, and Rod Stewart. The real flamboyant names were

the ones that lived through that and are still going, which is

great. We were total best of friends and everything, but we

were afraid to sit down and write anything together, I think,

‘cause we were always in competition. It was one of those

things where every time one of his albums came out, ours

came out.

On the album, “From The Inside” you seem to be having

a couple of digs at Los Angeles. would that be right?

Digs? No. I’m totally pro Los Angeles. Beverly Hills? I love

Beverly Hills. Wish I was born there.

That’s what it says, but the song seemed to be tongue in cheek.

I love phoniness. I love the idea that every single person in

Los Angeles has got an alternate motive. Everybody’s an

actor. All the cops watch television and so they all have

great haircuts. And they all talk like television cops, and

they’re great. I really like the Hollywood attitude. And L.A. is

my home. Every time I land in L.A. I feel at home. I saved

the Hollywood sign, that’s how much I love L.A. If I take a

dig at L.A., it’s certainly with a sense of humor that the

people there would understand. Anybody would wish that

they were born in Beverly Hills. It’s great. Born with a

diamond spoon in their mouth.

It would seem like your macabre side would be more appro-

priate for a place like New York than Los Angeles.

Yeah, but it’s not really. I lived in New York for a long time

and Ijust wasn’t at home there. I couldn’t live in the cata-

combs. I felt like I was in a hotel all the time, even if I was in

my apartment. I’m at home here in L.A.; I wouldn’t live any-

where else in the world. And that includes Beverly Hills,

Hollywood, everything. If I get outside of the perimeter of

Hollywood or Beverly Hills, I start feeling uncomfortable.

How did you meet your wife?

She was in the show. She was into ballet and other gran-

diose kinds of things and she didn’t even know who Alice

Cooper was. She really, honestly didn’t know. And when

she came to audition for the show and saw the spider cos-

tumes and all, it was a job, a good job, a hard touring job,

and she wanted to work.

She was a ministers daughter, wasn’t she?

Yeah. And I’m a minister’s son, so when we got married

both of our fathers performed the ceremony. It was great.

Our fathers are really good, too.

Do they approve of what you’re doing?

They’re real progressive, both of them are. They believe in

what they believe in, so I don’t hassle them about that. And

they don’t hassle me about this. My dad believes in my abil-

ity, and I think that’s a compliment to me. He knows more

about the top forty than I do, most of the time. He’ll call me

up and say, “Hey, listen, the Electric Light Orchestra just

went up three notches, and you only went up two, you

better . . .” And I’ll say, “what?”

Can you recall any moments in your career that really stand out?

So many things happened, you become like an institution. I

mean, they made me the Grand Marshall of the Mardi

Gras, all those sort of things. I made it into Who’s Who. The

only thing I haven’t really gotten yet is elected to the Amer-

ican League Hall of Fame. And I really want that.

There was a time in the mid-Seventies when you broke all

records touring around me country Is it hard to go back to a

position less than that?

Not at all. Because I did that. I already did that. And it’s a

different time, for one thing. Nobody does that anymore.

We drew one hundred and fifty-eight thousand people in

Brazil, indoors. If you start worrying “Gee, I sold this many

tickets last time, and I’m not so popular now,” you’re forget-

ting the fact that nobody has money out there. I’m on a

budget now.

Do you have any movie aspirations?

Well, after Roadie I’ve been offered a lot of things.

Are you looking forward to a movie career?

Oh, it’s going to be great. Again, I’ll never play the hero.

Vincent Price and Boris Karloff and many others made

careers from playing the villain.

Too many people want to be the hero. Let me be the villain.

I’ll be happy.